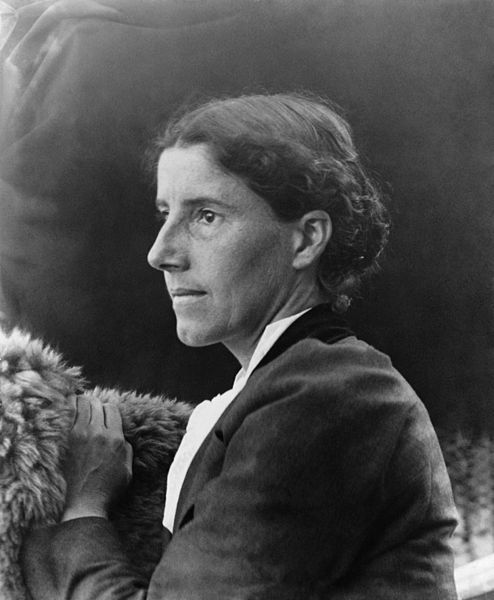

The issue of the personal and physical space of women looms large in A Room Of One’s Own (Woolf, 2014) and The Yellow Wallpaper (Gilman, 2013). Woolf emphasises the need for seclusion, whilst Gilman rallies against it when it is enforced. The key to this issue of space in these texts is the notion of control and autonomy; the relationship between the space accessible by the narrator’s in these texts is symptomatic of the social, legislative and economic structures that confine and prescribe their movement throughout their environment, and the kind of environments to which they are permitted access.

To establish the relationship between space and societal positioning in The Yellow Wallpaper and A Room of One’s Own it is important to highlight the social controls that can be directly linked to the use of space within these texts. Patriarchal control of education and finances relies on the isolation of women from places which would allow them to procure the means to self sufficiency and by result self determination.

The use of domestic space and room furnishings or decor as a focal point for the protagonists psychosis in The Yellow Wallpaper enter the realm of domestic coding in women’s literature (Radner and Lanser, 414) which follows in the tradition of women in literature being acutely aware of their domestic space due to the cultural conventions and roles they are expected to fulfil. It is a secret knowledge of the domestic that subverts the patriarchal control of information and power. In the case of The Yellow Wallpaper, Gilman’s narrator has an acute, painful and maddening obsession with the pattern in the wallpaper of her domestic prison, and whilst this obsession takes a delusional turn her initial dislike of the wallpaper is firmly rooted in the domestic, with the discussion of aesthetics and practicalities, but combined with her confinement grows into something much darker. Gilman reveals this progression gradually through the increasingly agitated reflections of the narrator;

It is the strangest yellow, that wallpaper! It makes me think of all the yellow things I ever saw-not beautiful ones like buttercups but old foul, bad yellow things.

– Gilman, 18

On the other hand Woolf’s insight into this preoccupation with the physical and domestic sphere allows her to reflect on the familial and household considerations that lie between women and academic or creative endeavours in a way that the student, Shakespeare and the gentlemen at the university can never properly fathom due to their limited exposure and negligible responsibilities in this field at this time.

Woolf goes into great detail about the importance of personal space for expression (Neely, 318) when any individual is endeavouring to create, most famously positing that “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” (Woolf, 11).

But the dominion that men hold over financial matters, both in Woolf’s time and, in particular, the times of her mother and her maternal ancestors (Woolf, 24) means that they also control access to space, making it near impossible for a woman to carve out a space for herself without the sanction or patronage of male benefactors. The academic and literary space that Woolf craves for women is expressed through the imagery of the simple room, she does not demand a luxurious space but a space free from the domestic subjugation of her foremothers and from the patronizing, sensational judgement of her gender by the scores of male authors whose works she notes in the library (Woolf, 31). Woolf in her perusal of these library shelves finds and absence of space for women; the judgement of women by men was well represented, but women authors had not even been allowed a small space upon a shelf purporting to be full of the most pertinent information about them. The male academic construction of woman as domestic, exotic or dangerous is made evident through the disappointing results of the narrator’s research and places women in society in roles entirely defined by the male perception of them. Masculine constructed views of women dominate the shelf space, in this library as they do outside it’s walls (Rosenman, 645).

This masculine control of space is also evident in The Yellow Wallpaper in which the husband controls the space his wife may inhabit, even within the boundaries of her own home (Ford, 309). John, her husband controls her physical space and her contact with the outside world, confining her to extended and enforced bedrest, despite her instincts to and desires that drive her, at least initially, to seek out life beyond her room;

I sometimes fancy that in my condition, if I had less opposition and more society and stimulus…

– Gilman, 5

Gilman’s narrator experiences a world full of barriers and segmentation in which people are divided inextricably into their allowed spaces, excepting white men of means who are able to come and go as they please, noted by John’s continued absence (Gilman, 11) and symbolic view the narrator has of the outside world;

There are hedges and walls and gates that lock, and lots of separate little houses for the gardeners and people

– Gilman, 5

In this passage she observes the segregation of gender and class that allows those in positions of power to maintain their superior status.

The use of the nursery in The Yellow Wallpaper as the place of the narrators confinement points to the infantilization of women in society, with her husband restricting her and enforcing rules in a parental fashion (MacPike, 287). She is also imprisoned using bars, not dissimilar to the bars she begins to see restraining the women in the patterns of the wallpaper. Her room is also symptomatic of her complete lack of control in the face of her husband’s authority; She does not choose the room and she does not choose her space in life (MacPike, 288). She expresses her desire to leave, she expresses her desire to be away from the wallpaper, but her simple request is greeted with a patronizing rejection and a reminder that she has to defer to her more educated and authoritative doctor husband (Gilman, 15).

Woolf also explores the infantilizing of women as she is shoed off the grass by the bursar and the confining of women to the home and domesticity. It is also a theme that is evident as she theorises about what will happen if the power imbalance is rectified and women are no longer shielded like children; “Anything may happen when womanhood has ceased to be a protected occupation.” (Woolf, 40)

By placing women in the home and likening them to children, they are denied adult autonomy and sexuality. The fear and fetish that lies at the heart of the masculine construction of women found in A Room of One’s Own, with the scholarly works she touches on “[enshrining] male prejudices against women” using their sexuality as weapons against them or denying feminine sexuality almost entirely (Rosenman, 645).

The protection and infantilization of women also extends to access to information and education. Woolf demonstrates the of the denial of education, particularly higher education (Wall, 189) to women in the barring of Woolf’s framing narrator to the space within the university. The lack of access to coveted and traditionally male domains in the framing narrative of A Room of One’s Own reflects the rejection of women from places and positions of power and access to important resources that would allow an meaningful feminine impact on society, art and culture. To emphasize these barriers Woolf invokes imagery of locked doors; a motif that also appears in Gilman’s text.

Gilman’s narrator, as the narrative progresses and her psychological break begins to reveal itself, not only begins to see women trapped beneath the wallpaper as she is in the room but eventually recognises herself as being one of the women trapped in the wallpaper, making a space for herself and other trapped women in a space where she is confined unwillingly;

I don’t like to look out of the windows even–there are so many of those creeping women, and they creep so fast.

I wonder if they all come out of that wallpaper as I did?

– Gilman, 23

The relationship between the access the women of these texts have to space is tied to the methods of control used to keep women out of the establishments and dominions of men, whether on a conscious or subconscious level. The results of the suppression of feminine influences outside the home is detailed within these texts; from the mediocrity of Mrs Seton and the disappointments of Mary Shakespeare in Woolf’s essay, to the imprisonment and psychotic meltdown of the narrator in Gilman’s short story. The limiting and restricting of feminine space in these texts allows a glimpse into the importance of both literary and real world space in the maintenance of masculine power and social control.

Written by Morgan Pinder

References

• Ford, Karen. “‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ and Women’s Discourse.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 4, no. 2, 1985, pp. 309–314., http://www.jstor.org/stable/463709.

• Gilman, C. (2013). The Yellow Wallpaper. 1st ed. London: Harper Collins.

• MacPike, Loralee. “Environment as Psychopathological Symbolism in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper.’” American Literary Realism, 1870-1910, vol. 8, no. 3, 1975, pp. 286–288., http://www.jstor.org/stable/27747980.

• Neely, Carol Thomas. “Alternative Women’s Discourse.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 4, no. 2, 1985, pp. 315–322., http://www.jstor.org/stable/463710.

• Radner, Joan N., and Susan S. Lanser. “The Feminist Voice: Strategies of Coding in Folklore and Literature.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 100, no. 398, 1987, pp. 412–425., http://www.jstor.org/stable/540901.

• Rosenman, Ellen Bayuk. “Sexual Identity and ‘A Room of One’s Own’: ‘Secret Economies’ in Virginia Woolf’s Feminist Discourse.” Signs, vol. 14, no. 3, 1989, pp. 634–650., http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174405.

• Wall, Kathleen. “Frame Narratives and Unresolved Contradictions in Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own.’”Journal of Narrative Theory, vol. 29, no. 2, 1999, pp. 184–207., http://www.jstor.org/stable/30225727.

• Woolf, V. (2014). A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas. 1st ed. London: Harper Collins UK, pp.10-99.

Leave a comment